From the inception of the city, Seneca was established as a diverse community atypical to rural life in the Deep South. Of the sixteen lots sold at the town’s first land auction on August 14, 1873, two were purchased by African Americans. David Singleton and Elisa and Willis Jenkins purchased lots #5 and #50 for $120.00. Mr. Singleton was listed as a carpenter in the 1880 U.S. Census.

Prior to the rise of the Jim Crow era in southern states, residents in Seneca City lived in integrated neighborhoods and conducted business across racial lines. Many of the African American residents were business owners and skilled craftspeople. But, as segregation and racial bias began to take hold, census records indicate a definitive shift and once-integrated streets and neighborhoods drew lines of division based on race. Even so, African Americans had a significant impact on building the city and left an enduring legacy.

Early African American Business

Adams Funeral Home Staff A group photo of the Adams Funeral Home staff in 1971. Peek & Addison Funeral Home/Adams Mortuary was founded in the early 20th century by Willie Peek of Anderson and William D. Addison of Seneca. Addison and his family ran the Addison Funeral home till his death in 1978 when it became the Adams Mortuary. Adams Mortuary is now owned and operated by Mr. Irvin Brown and his son, Grady Brown of Seneca.

Addison Family Photograph of William Addison, his wife, and daughter inside their home. Addison founded the Addison Funeral Home in 1925.

Office of Dr. Battle (North Walnut Street Seneca, SC) Dr. Charles T. Battle Jr. (1919-1998): An Alabama native, Dr. Charles T. Battle taught public school before receiving his medical degree in 1950. In July 1954 he and his family moved to Seneca to open his medical practice which stayed open until he retired in 1992. Dr. Battle was one of the first African American doctors to work for Oconee Memorial Hospital joining the staff there in 1956. The photo taken in 1955 shows the office of Charles T. Battle Jr., MD (left) and Harry Thomas Sr., DDS (right). The Battle Clinic relocated to the corner of Oak and West South 3rd Street in Seneca.

Dr. Sharp Dr. Bryant Sebastian Sharp (1877-1956): Born in Seneca to a farming family, Dr. Bryant S. Sharp (right) attended the Seneca Institute before earning his medical degree at Leonard Medical College in 1906. He returned to Seneca that same year to start his practice and was Seneca’s first African American doctor.

Johnson-Cureton Funeral Home Johnson-Cureton Funeral Home - South Oak Street Seneca, SC - Undated

Piedmont Pharmacy Founded in 1937 by Dr. Harold E. Hill and Dr. B.C. Sharp of Seneca, Piedmont Pharmacy was the only pharmacy for African Americans in Oconee County. The pharmacy’s soda fountain/sandwich shop served the African American community and was one of the places where Harvey Gantt would eat when he was a student at Clemson University. The pharmacy was originally located on East Main Street in downtown Seneca.

One of the most significant legacies that, according to the book, Byegone Days, by author and local historian, the late D. Land ("Renaissance Man") is the naming of Ram Cat Alley in historic downtown Seneca. Mr. Land penned in his book that an African American man named Peter Major and his wife Mollie ran a fresh fish market and grocery store during the late 1800s. Mr. Major sold fresh fish on the alley street and had so many cats trailing the scent of the fish each day that folk started saying that you “couldn’t ram another cat on the alley.” So, eventually, the block-long street became known as Ram Cat Alley. Mr. Major lived in Walhalla and in 1899 became President of the Colored Industrial Association of Oconee County. He also owned a grocery store in West Union, SC.

Another early African American Oconeean was Liz Starks who was a horse-trader. Livestock sales were held regularly in downtown during the city’s early years.

After the turn of the 20th century, W.J. Thomas an African American educator from Seneca started the county’s only African American owned newspaper, The Southern Monitor, where he also served as the paper’s editor. W.J. Thomas was the father of Dr. Harry Thomas Sr., who became the first African American dentist in Seneca.

Mr. Saul P. Wakefield, an African American Senconean, ran a general store on the corner of Ram Cat Alley and Townville Street that he opened in 1883. The store was destroyed in the 1890 downtown fire. He rebuilt the store and successfully operated it until 1899.

December Gadsden was a well-respected blacksmith who owned and operated a blacksmith stand in downtown Walhalla, SC. He was born in 1840 and was also a wagon maker. He owned and operated a Dance Hall (Gadsden’s Hall) near the property where New Galilee Baptist Church now stands. He was known in the area for the delicious fruit from his pear trees. One news article mentioned that Thomas E. Miller, President of SC State College, along with his wife and children were guests in his home during their visit to Walhalla.

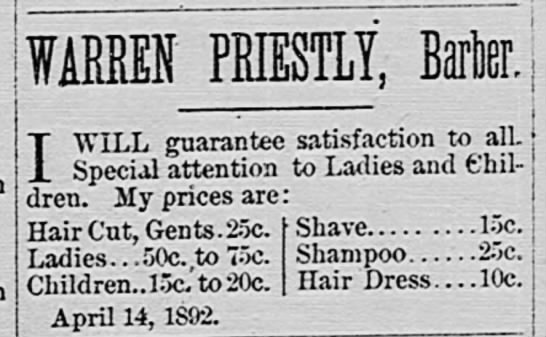

Warren Priestly (1847-1904) and Willis James (1868-1930) were barbers who ran their own businesses in Walhalla. Mr. Priestly’s establishment was located on Main Street and was fitted with two of the latest barber chairs. For more than 25 years, Mr. Priestly was the leading barber in Walhalla, SC. Mr. James’ business was located inside the Walhalla Hotel on Main Street and was equipped with a new “Koken revolving chair” and an “automatic fan.” The two eventually joined forces and became known across the state for their skillful artistry and handsome quarters.

One of the most prominent African American businessmen in Oconee County around the turn of the century was Mr. Elias Kibler, Sr. Born in 1866, Mr. Kibler later became owner and operator of one of the largest farms in the county. He started as a tenant farmer who in 1895 lost everything he had when his landlord repossessed the property, crops, and even a beehive as collection for the debt Mr. Kibler owed to him. Years after, Mr. Kibler would save enough money to buy a small 60-acre farm and three mules. He began farming cotton and in 1907 bought the entire 288 and ¾ acre farm from which he was previously evicted. He eventually employed local hires and his crops included grain, peas, soybeans, cotton, corn, sweet potatoes, chickens, turkeys, hogs and cattle including a registered Jersey Bull. He also cooperated with a government agent in grass growing and sold produce to Clemson College. Elias Kibler senior was known for using the best and latest improved machinery and employed other African Americans to whom he also provided housing. Eighteen years after being evicted from his home, Mr. Kibler had acquired property worth approximately $20,000 (equivalent to more than $525,000 in 2020). The father of nine, Elias Kibler, Sr., was described by his white neighbors as “a worthy citizen who… lives under his own fig tree and none molests him or makes him afraid.”

Race Demographics for Oconee County (by percentage)

African American businesses continued to thrive in Oconee County during the segregated Jim Crow era. Because neighborhoods had become separated by race and African Americans were no longer allowed to trade at many white-owned businesses, entrepreneurship among African Americans flourished. These African American-owned businesses supplied the needs of their community and included physicians, dentists, ministers, farmers, nurses, teachers, grocery store owners, retailers, hairstylists, barbers, plumbers, electricians, appliance repairmen, carpenters, morticians, restaurant owners, club owners, craftsmen, and more. African American neighborhoods became self-sustaining and self-sufficient and their business communities flourished. However, during the Great Depression (1929-1939) and during the second wave of the Great Migration (1940-1970) many African Americans from the upstate of South Carolina headed north and west to seek better economic opportunities and to escape harsh segregationist laws established in southern states. In fact, prior to 1920, South Carolina’s African American population exceeded the state’s white population.

Although no complete list of Oconee’s African American businesses has ever been compiled, the Carter Archives of the Bertha Lee Strickland Cultural Museum is making strides in creating such a list. Through oral histories, census records, and other reliable sources, an evolving list of businesses, business owners, craftspeople and tradespeople are being documented and preserved.

So far, the list of African American former business owners/operators in Oconee County over the past 150 years include:

| Business Owner | Business | Location |

|---|---|---|

| William Addison | Addison Funeral Home | Seneca |

| Willis James | Barber | Walhalla Hotel |

| Warren Priestly | Barber | Walhalla Hotel |

| Conrite Hallums, Sr | Barber (Late 20th Century) | Westminster |

| William Bradley | Barber Shop | Walhalla |

| Willie Grant | Barber Shop | Seneca |

| Andy Gray | Barber Shop | Seneca |

| Terry Jenkins | Barber Shop | West Union |

| Henry Williams | Barber Shop | Oak St. Seneca |

| Aleck Z. Flemming | Barber Shop (Late 1800s/early 1900s) | Seneca |

| Charles T. Battle, MD | Battle Clinic (Mid-Late 20th Century) | Seneca |

| Ezekiel H. Hendrix | Blacksmith | Westminster |

| December Gadsden | Blacksmith/ Dance hall operator (1880s-1910s) | Walhalla |

| R.B. Burns | Burns Grocery Store | Seneca |

| William H. Gaines, Sr. | Café | Seneca |

| James Telley | Café | Walhalla |

| Henrietta Young | Café | Seneca |

| Laylon Wilson, Sr. | Café (Late 20th Century) | Westminster |

| B.T. Scott | Carpenter (1940s) | Seneca |

| John W. Beeks | Cobbler/Retail shoe rebuilding | Seneca |

| William Cureton, Sr., & David Morris | Cureton & Morris TV Repair (Late 20th Century) | Seneca |

| William Cureton, Sr. | Cureton TV Repair (Late 20th Century) | Seneca |

| James E. Terry | Drayman | Seneca |

| Drs. Henry J. Hare & Amon A. Martin, DDS | Drs Hare and Martin, PA (Late 20th Century) | Seneca |

| Charlie Norton | Dry Cleaners | Walhalla |

| Samuel Greer/Green | Dry Cleaners (early 1900s) | Seneca |

| Robert Hix | Farm Store Proprietor | Seneca |

| Elias Kibler | Farming-Commercial (1900s) | Seneca |

| Otis Grant | Farming-Commercial (Late 20th Century) | Westminster |

| Peter and Molly Major | Fish Market/Grocers (Late 1800s) | Ram Cat Alley-Seneca & West Union |

| Alphonso Gaines, Sr. | G & J Store (Late 20th Century) | Seneca |

| Doyle Gilbert | Gilbert Funeral Home | Seneca |

| Claude Earle | Grocery Store | Seneca |

| Alice G. Long | Grocery Store | Seneca |

| Arminus Perry | Grocery Store | Westminster |

| William Williams | Grocery Store | Seneca |

| Simpson & Lone | Grocery Store (Late 1800s/early 1900s) | West Union |

| Francis Oliver | Hairdresser (Late 20th Century) | Seneca |

| Roseana Spencer | Hairdresser (Late 20th Century) | Seneca |

| Alice Kibler | Hairdresser (Late 20th Century) | Westminster |

| Waymon Hallums | Hallum's Dry Cleaners (Late 20th Century) | Seneca |

| Liz Starks | Horse Trader (Late 1800s) | Seneca |

| George Green | Ice Factory (1930s); Restaurant (1940s) | Seneca |

| Parmel Jenkins | Jenkins Place Café | Walhalla |

| Mr. Gilbert | Johnson-Cureton Funeral Home | Seneca |

| Kirksey Williams | Mechanic | Seneca |

| Grady Thompson | Mechanic Shop (c. 1950-60) | Seneca |

| Benjamin R. Ware, Sr. | Men's Clothing Store and Barber Shop (1900s) | Seneca |

| William A. Jenkins | Merchant | Seneca |

| Joe Love | Merchant- General Store | Seneca |

| S.P. Wakefield | Merchant/General Store (1883-1899) | Ram Cat Alley, Seneca |

| George C. Scott | Notion Store/Thrift Store (Early 1900s) | Seneca |

| Dr. B. C. Sharp | Piedmont Pharmacy | Seneca |

| Dr. Bryant Sebastian Sharp | Physician | Seneca |

| Dr. Harold E. Hill | Piedmont Pharmacy & Hill's Pharmacy | Seneca |

| Dr. Harry E. Thomas, DDS | Dentist | Seneca |

| Jesse Kilpatrick | Pressing Club Owner (clothes pressed and groomed) | Seneca |

| Estelle Derrik | Restaurant | Seneca |

| Darling L. Latimer | Shoe Rebuilder | Seneca |

| Charles Wright | Shoe Shop | Seneca |

| Harry C. Jones | Superior Funeral Home (Late 20th Century) | Seneca |

| W.J. Thomas | The Southern Monitor Newspaper (Early 1900s) | Seneca |

| Esther Williams | Washerette (c. 1950-60) | Seneca |

Desegregation in Oconee County began in the late 1960s and became well-established throughout the county during the 1990s. 21st Century entrepreneurship among African American Oconeans is once again increasing. Family foundations and other non-profits run by African Americans are being introduced to serve the county’s growing diverse population. These foundations and non-profits include:

Current Foundations and Non-Profits

Annie Lois Davis Foundation

The NOLA Network

Blue Ridge Community Center

Seneca

Seneca

Seneca

The Seneca City Museums are working continuously to compile a complete history of African Americans in Oconee County. We invite anyone with additional or updated information about Oconee’s African American businesses past or present to CONTACT US.